Why interconnectedness describes the world, and interbeing changes it

(Global Heart) We live in the age of the Internet, of globalization, and of climate change. We know, intellectually, that everything is linked. So why do we continue to act as if we are separate? This paradox is the starting point for exploring the two foundational truths of existence: Interconnectedness and Interbeing. One is the scientific fact; the other is the spiritual practice. Understanding the distinction is the key to transforming our world.

“We need the vision of interbeing—we belong to each other; we cannot cut reality into pieces. The well-being of “this” is the well-being of “that,” so we have to do things together. Every side is “our side”; there is no evil side.” ― Thich Nhat Hanh, Peace Is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life

The fabric of reality: Interconnectedness versus interbeing

In a world grappling with ecological collapse, social fragmentation, and pervasive loneliness, understanding the concept of connection has never been more vital. But is the widely accepted idea of ‘interconnectedness’ enough to solve our crises? This article explores the two foundational truths of existence: the descriptive reality of Interconnectedness and the transformative path of Interbeing.

What is the meaning of interconnectedness?

Interconnectedness is the state of being mutually or reciprocally connected. In its broadest sense, it describes the profound truth that nothing exists in isolation; every entity, idea, event, or system is part of a larger web of relationships, influencing and affecting one another.

Interconnectedness describes a foundational reality across all fields, from physics to philosophy. It emphasizes three key aspects:

- Mutual connection: It signifies a two-way or multi-directional link where things rely on each other for their existence and function.

- A larger system: It suggests that individual parts belong to a greater whole, and true understanding requires seeing the relationships between the parts, not just the parts themselves.

- Impact and ripple effect: Actions or changes in one area inevitably have consequences that ripple out to other connected areas.

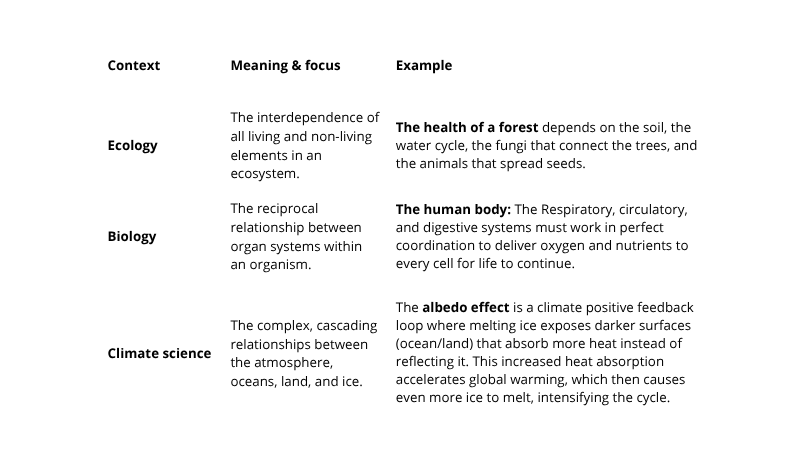

Interconnectedness in different contexts

The concept appears in many fields, highlighting its fundamental nature:

- Ecology & science: The interdependence of all living and non-living elements in an ecosystem. The health of a forest depends on the soil, the water cycle, the animals that spread seeds, and the fungi that connect the trees.

- Society & economics: How people, communities, and nations are linked through trade, culture, and shared challenges. Globalization is a clear example, where a financial crisis in one country can quickly impact markets across the world.

- Philosophy & spirituality: The idea that all beings are fundamentally unified and that our individual existence is relational, not separate. Think of the Buddhist idea of dependent origination or the African philosophy of Ubuntu (“I am because we are”). |

- Technology: The linking of devices, networks, and information, such as the Internet or the Internet of Things (IoT). For example, a simple software update on one network server can affect millions of users and devices globally.

The significance of recognizing interconnectedness

Understanding interconnectedness is crucial because it leads to a shift in perspective, encouraging:

- Holistic thinking: Looking at problems or systems as a whole, rather than just isolated parts.

- Empathy and compassion: Recognizing our connection to others fosters a sense of shared well-being and responsibility.

- Responsible action: Understanding the far-reaching consequences of our choices (e.g., in environmental impact or social policy).

The meaning of interbeing

The deepest and most transformative understanding of interconnectedness comes from the late Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh, who coined the term “interbeing” to make this concept actionable and accessible.

Interbeing is a translation of the core Buddhist teaching of pratītyasamutpāda (dependent co-arising). Thich Nhat Hanh recognized that the verb “to be” implies a singular, independent existence (“I am”), which he saw as the root of human suffering and ecological crisis.

He replaced it with a new verb: “to inter-be.”

“To be is to inter-be. You cannot be by yourself alone. You have to inter-be with everybody and everything else.”

— Thich Nhat Hanh

The Illustration of the paper

Thich Nhat Hanh famously used the example of a single sheet of paper to illustrate the word ‘interbeing’:

- Look deeply: When you look at the paper, you cannot see it existing by itself.

- You see the Cosmos: If you look closely, you see the sunshine that nourished the forest, the rain and clouds that fed the tree, the soil and minerals, the labor of the logger and the mill worker, and even the history that led to its creation.

- Conclusion: Without these “non-paper” elements—the sun, the clouds, the ancestors—the piece of paper cannot exist. The paper is therefore empty of a separate self, yet full of the entire cosmos. It inter-is with everything.

The significance of interbeing

This insight transforms perspective, leading to:

- Holistic thinking: Recognizing that you are not separate from your environment or your community.

- Compassion and peace: Understanding that “their suffering is not separate from your own.” To help another person is to heal a part of the greater system you belong to.

- Ecological responsibility: Realizing that the environmental crisis is a crisis of perception. Harm to the Earth is harm to our own body, because we are made of the same elements.

Interconnectedness in the natural world

The concept is a core operating principle in science:

In short, interconnectedness is the descriptive term for this reality, while Interbeing is the transformative, active realization of this truth.

From separation to engagement

Thich Nhat Hanh’s vision is a direct application of this insight to three critical areas:

1. Compassion and peace (internal interbeing)

The illusion of a separate self—the idea that “my suffering is mine alone” or “your happiness has nothing to do with me”—is the fuel for all conflict and loneliness.

When you understand that you inter-are with another person, their suffering is not separate from your own. To help them is to heal yourself.

The practice of mindfulness becomes the tool to recognize this connection in the present moment, transforming fear and anger. When we see the suffering that led a person to cause harm, we are no longer separate from them; we see the causes and conditions (the “non-self” elements) that led to their action. This does not excuse the action, but it creates the space for genuine compassion and non-violent transformation.

2. Ecological responsibility (planetary interbeing)

For Thich Nhat Hanh, the environmental crisis is primarily a crisis of perception. We treat the Earth as something separate from us—a reservoir of resources we can exploit—because we believe we are separate individuals.

The insight of interbeing makes environmentalism a form of self-care. When you look at a polluted river, you see the water you drink; when you look at a clear-cut forest, you see the air you breathe.

He taught that we must “fall back in love with the Earth” by recognizing it as our true home and our shared body. Harm to the “animal, vegetable, and mineral life” is harm to the human body, for we are made of these very elements. Interbeing, therefore, provides an ethics for the Anthropocene.

3. Collective awakening (The next Buddha is a Sangha)

Thầy believed that individual salvation is impossible in a suffering world. The solution to global challenges like war, poverty, and climate change will not come from a single, heroic figure.

His vision was that the next Buddha shall not be an individual; the next Buddha shall be a community (Sangha) practicing mindfulness and deep looking together.

Only through the collective energy of a community living and practicing the insight of Interbeing can we generate the wisdom and compassion powerful enough to solve the world’s systemic problems. It requires a shift from consumerist individualism to communities of interbeing.

How can we bridge the gap between the intellectual understanding of Interbeing and the emotional experience of a seemingly separate self?

Bridging the gap: From concept to embodied insight

The difficulty lies in the fact that our senses, our language, and our biological conditioning are built on the principle of differentiation (survival requires distinguishing ‘me’ from ‘not me’). Thich Nhat Hanh addressed this challenge not with more philosophy, but with practices—simple, actionable methods for “looking deeply” that train the mind to override the illusion of separation.

Here is how Thich Nhat Hanh suggests bridging that gap, moving from a subtle concept to a lived reality:

1. The practice of deep looking (or meditation)

The realization of Interbeing is not an emotional feeling but a moment of insight (vipassanā). This insight is achieved through mindful concentration, or “Deep looking.“

- Go beyond logic: Thich Nhat Hanh taught that Interbeing is not achieved by logically trying to trace every connection (e.g., “how is this speck of dust on Mars connected to me?”). That process relies on the separate, analytical mind.

- Object meditation: Instead, you choose a simple object—a piece of bread, a flower, your own hand—and use the energy of mindfulness to look into it, not at it. You allow the object to reveal its constituents.

- Actionable step: Hold a flower. Breathe in and out, calming your mind. Then, gently ask: “Where is the cloud in this flower? Where is the soil? Where are the invisible elements of time and space?” Do not answer with your intellect. Simply allow your awareness to rest on the flower until the non-flower elements begin to appear not as a mental list, but as an organic, inseparable presence. This direct seeing dissolves the illusion of its separate identity.

2. Practicing non-self

- The attachment to a permanent, unchanging “I” is the core of the illusion, often reinforced by our biological drive for individual survival. This flawed perception can only be dissolved through the liberating experience of Non-Self (anattā).

- Recognize your continuation: If you feel like a separate, isolated entity, remember all the “non-self” elements that make you possible. You are not a solitary being. You contain your parents, your grandparents, the food you ate this morning, the air you just breathed, and the Earth you stand on.

- Actionable step: During mindful walking or sitting, breathe in and know that “I am a continuation.” See yourself not as an isolated unit, but as a vast current of energy, ancestors, and elements constantly flowing and changing. This practice shifts the perspective from a solid, fearful “me” to a spacious, fearless “us.” You realize that what we called the “false” is simply the temporary manifestation, not the underlying reality.

3. The practice of interpersonal reflection

The strongest illusion of separation occurs between “me” and “you.” Thich Nhat Hanh’s practices emphasize dissolving this boundary in relationships.

- Using conflict as a teacher: When you feel anger or judgment toward another person, that is the moment to look deeply.

- Actionable step: Ask yourself: “What are the non-person elements that made this person act this way?” See their history, their ancestors, their environment, their suffering, and their stress. By seeing the causes and conditions outside of their alleged “self,” you stop judging them as a fixed, independent villain. You realize that their suffering, and the actions born from it, are a product of the collective, meaning you, too, are connected to the conditions that led to their pain. This is the moment when compassion naturally arises, because the separation breaks down.

The realization of interbeing is not something to believe but something to practice and see again and again, until the subtle, conceptual understanding becomes the undeniable, lived reality of your existence.

Engaged Buddhism and the power of non-fear

Thich Nhat Hanh coined the term “Engaged Buddhism” during the Vietnam War. It represents a movement that applies Buddhist teachings—specifically the insights of Interbeing, compassion, and non-violence—to address social, political, and environmental suffering. It is the realization that if we inter-are, then our spiritual practice cannot be separate from the world’s suffering.

The foundation of Engaged Buddhism is the understanding that true peace is not merely the absence of war, but the cultivation of justice, understanding, and compassion in the face of systemic suffering.

The two powerful questions:

- Am I truly nourishing myself and supporting the life on Earth?

- Am I feeding the seeds of joy and peace, or the seeds of sorrow and violence, in myself and in the world?

To truly engage with the world’s problems—climate change, social injustice, political polarization—we must confront the deepest obstacle: Fear.

Thich Nhat Hanh taught that the source of fear is the illusion of a separate, permanent self. We fear loss, death, and annihilation because we cling to the idea that the “I” is solid and independent.

Engaged Buddhism is the way we bring the light of Interbeing into the darkness of the world. It reminds us that to change the world, we must first change our consciousness, and that personal awakening and global healing are a single, unified path.

Source: Global Heart

You may also like:

Thich Nhat Hanh on finding peace

Thich Nhat Hanh on non-duality and the consciousness of ‘things’