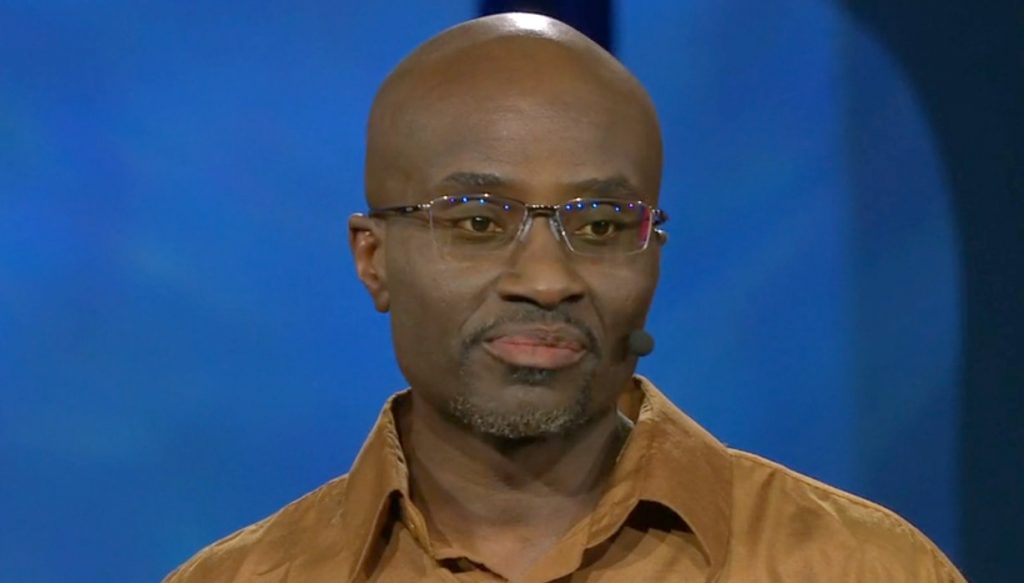

How I unlearned dangerous lessons about masculinity

(Ted) Big boys don’t cry. Suck it up. Shut up and rub some dirt on it. Stop crying before I give you something to cry about. These are just a few of the phrases that contribute to a disease in our society, and more specifically, in our men. It’s a disease that has come to be known as “toxic masculinity.” It’s one I suffered a chronic case of, so much so that I spent 24 years of a life sentence in prison for kidnapping, robbery, and attempted murder.

How I unlearned dangerous lessons about masculinity

Yet I’m here to tell you today that there’s a solution for this epidemic. I know for a fact the solution works, because I was a part of human trials. The solution is a mixture of elements. It begins with the willingness to look at your belief system and how out of alignment it is and how your actions negatively impact not just yourself, but the people around you. The next ingredient is the willingness to be vulnerable with people who would not just support you, but hold you accountable.

But before I tell you about this, I need to let you know that in order to share this, I have to bare my soul in full. And as I stand here, with so many eyes fixed on me, I feel raw and naked. When this feeling is present, I’m confident that the next phase of healing is on the horizon, and that allows me to share my story in full.

For all appearances’ sake, I was born into the ideal family dynamic: mother, father, sister, brother. Bertha, Eldra Jr., Taydama and Eldra III. That’s me. My father was a Vietnam veteran who earned a Purple Heart and made it home to find love, marry, and begin his own brood. So how did I wind up serving life in the California prison system? Keeping secrets, believing the mantra that big boys don’t cry, not knowing how to display any emotion confidently other than anger, participating in athletics and learning that the greater the performance on the field, the less the need to worry about the rules off it. It’s hard to pin down any one specific ingredient of the many symptoms that ailed me.

Growing up as a young black male in Sacramento, California in the 1980s, there were two groups I identified as having respect: athletes and gangsters. I excelled in sports, that is until a friend and I chose to take his mom’s car for a joyride and wreck it. With my parents having to split the cost of a totaled vehicle, I was relegated to a summer of household chores and no sports. No sports meant no respect. No respect equaled no power. Power was vital to feed my illness. It was at that point the decision to transition from athlete to gangster was made and done so easily. Early life experiences had set the stage for me to be well-suited to objectify others, act in a socially detached manner, and above all else, seek to be viewed as in a position of power. A sense of power equaled strength in my environment, but more importantly, it did so in my mind. My mind dictated my choices.

My subsequent choices put me on the fast track to prison life. And even once in prison, I continued my history of running over the rights of others, even knowing that that was the place that I would die. Once again, I wound up in solitary confinement for stabbing another prisoner nearly 30 times. I’d gotten to a place where I didn’t care how I lived or if I died.

Initially, yeah, that was a little much, but eventually, I overcame my hesitancy. As it turned out, the circle was the vision of a man named Patrick Nolan, who was also serving life and who had grown sick and tired of being sick and tired of watching us kill one another over skin color, rag color, being from Northern or Southern California, or just plain breathing in the wrong direction on a windy day.

Circle time is men sitting with men and cutting through the bullshit, challenging structural ways of thinking. I think the way that I think and I act the way that I act because I hadn’t questioned that. Like, who said I should see a woman walking down the street, turn around and check out her backside? Where did that come from? If I don’t question that, I’ll just go along with the crowd. The locker-room talk. In circle, we sit and we question these things. Why do I think the way that I think? Why do I act the way that I act? Because when I get down to it, I’m not thinking, I’m not being an individual, I’m not taking responsibility for who I am and what it is I put into this world.

It was in a circle session that my life took a turn. I remember being asked who I was, and I didn’t have an answer, at least not one that felt honest in a room full of men who were seeking truth. It would have been easy to say, “I’m a Blood,” or, “My name is Vegas,” or any number of facades I had manufactured to hide behind. It was in that moment and in that venue that the jig was up. I realized that as sharp as I believed I was, I didn’t even know who I was or why I acted the way that I acted. I couldn’t stand in a room full of men who were seeking to serve and support and present an authentic me. It was in that moment that I graduated to a place within that was ready for transformation.

For decades, I kept being the victim of molestation at the hands of a babysitter a secret. I submitted to this under the threat of my younger sister being harmed. I was seven, she was three. I believed it was my responsibility to keep her safe. It was in that instant that the seeds were sown for a long career of hurting others, be it physical, mental or emotional. I developed, in that instant, at seven years old, the belief that going forward in life, if a situation presented itself where someone was going to get hurt, I would be the one doing the hurting. I also formulated the belief that loving put me in harm’s way. I also learned that caring about another person made me weak. So not caring, that must equal strength. The greatest way to mask a shaky sense of self is to hide behind a false air of respect.

Sitting in circle resembles sitting in a fire. It is a crucible that can and does break. It broke my old sense of self, diseased value system and way of looking at others. My old stale modes of thinking were invited into the open to see if this is who I wanted to be in life. I was accompanied by skilled facilitators on a journey into the depths of myself to find those wounded parts that not only festered but seeped out to create unsafe space for others. At times, it resembled an exorcism, and in essence, it was. There was an extraction of old, diseased ways of thinking, being and reacting and an infusion of purpose.

I was paroled in June 2014, following my third hearing before a panel of former law-enforcement officials who were tasked with determining my current threat level to society. I stand here today for the first time since I was 14 years old not under any form of state supervision. I’m married to a tremendous woman named Holly, and together, we are raising two sons who I encourage to experience emotions in a safe way. I let them hold me when I cry. They get to witness me not have all the answers. My desire is for them to understand that being a man is not some machismo caricature, and that characteristics usually defined as weaknesses are parts of the whole healthy man.

So today, I continue to work not just on myself, but in support of young males in my community. The challenge is to eradicate this cycle of emotional illiteracy and groupthink that allows our males to continue to victimize others as well as themselves. As a result of this, they develop new ways of how they want to show up in the world and how they expect this world to show up on their behalf.

Source: TED

You may also like:

The wisdom within: sacred masculine and sacred feminine

Scientific evidence that your intentions and thoughts alter your physical world