The Shamanic view of Christmas

(Uplift) Have you ever wondered where the tale of Santa Claus came from? When you really think about it, the jolly old man in red and white, who travels on his sleigh pulled by flying reindeer to deliver gifts to children all over the world, is a pretty fantastical notion. Where did this intriguing tale, that is so widely known across the globe, start?

View of Christmas

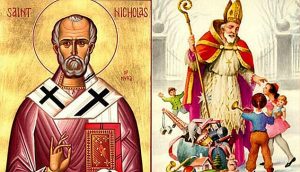

We’re told that he is based on Christian Saint Nicholas, who was known for his extensive generosity and good charity in the 4th Century, in modern-day Turkey. This idea – whilst not directly tied with the story of Jesus’ birth – still ties in nicely with the Christian faith, as good ol’ Saint Nick is said to represent love and charity, as well as good faith, having been a devout Christian himself. It is said that the Dutch adopted Saint Nicholas – whom they called Saint Nikolaas, and later birthed the nickname Sinterklaas – and brought his legacy to America in the 1700s.

But what if I told you there’s another story; one that explains the bizarre traditions of our white-bearded, present-bearing, fur-clad, chimney-descending friend, and more? This story begins in a land far, far away; a land in the North that’s covered in snow, where reindeer freely roam. “Ah yes – the North Pole!” you say, but alas, this is not the land that I speak of. This story starts not with old Saint Nick, but instead with a Shaman. A Shaman that descended down smoke holes in snow-covered homes, carrying medicinal red and white mushrooms to give to the cold families that inhabited them, during the unforgiving winter solstice.

Shamans and their practices

Picture this – we’re in Siberia, pre-expansion of the Russian empire in the 17th Century, a country that is known for its vast landscape, and harsh Northern winters. Here dwelled many tribes of Indigenous peoples and, like many ancient civilizations, these tribes had ‘Shamans’ that lived amongst their communities. Shamans can be described as ‘Medicine Men’, and were known to be powerful beings who could cross into different realms, and could use their special abilities to heal people in need.

Shamanism, although perhaps not quite as prevalent in the present-day world, is still evident in numerous First Nation cultures around the globe. From the Mayans in Central America to the Inuits in North America. From Indigenous Australians to the Maoris of New Zealand and from the Celts of the British Isles, all the way through to Africa, to mention just a few. These folk were revered amongst their peoples and were regarded with the utmost respect. Shamans were considered essential in a community, as they not only helped the ill and dying but were respected advisors and were often turned to for important decisions.

In their healing practices, Shamans commonly used – and still use – plants as medicine. Many of us are aware of the common uses of herbs and spices for minor ailments, such as turmeric for it’s anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial properties. But if you go deeper and explore the practices of true Shamans, you would find that they work with powerful plants; mind-altering plants that are said to have the ability to connect them to alternate realities. I’m talking about plants like Ayahuasca, medicinal mushrooms, Washuma, and many more, depending on where in the world you are. The thing that many of these plants have in common, is that they are what we know as psychedelics.

Whilst in the Western world, man-made psychedelics are used for a ‘trip’; escapism or just for fun, Shamans use them in their natural form as a way to connect with Spirit, Source, higher self (and so on) where they can access information and realities beyond the physical one that we see and know in our daily lives. Siberian Shamans typically used a fungus.

Magic mushrooms at Christmas time

Amanita muscaria, known more commonly in the West as a ‘magic mushroom’ or ‘toadstool’, is a native of Siberia, among other regions of the world. These bright red mushrooms with their pretty white specks have long been associated with folk tales of fairies and other mystical creatures, but also make an annual appearance at Christmas time. Many of us have seen the Christmas paraphernalia in which they feature, and I’m sure many of you currently have the adapted versions – red and/or white baubles – hanging from the branches of your Christmas tree. Well, ethnographers have discovered notable evidence that this is no mere coincidence.

Amanita muscaria, like other Shamanic plant medicines, are indeed hallucinogens. The psychedelic compounds are muscimol and ibotenic acid and, if eaten raw, the mushrooms can cause sweating, nausea, chills, salivation, and vomiting. But when dried or boiled before consumption, the chemical make-up is changed and the effects become milder, creating a sense of inebriation, impaired balance, euphoria, and increased clarity of thought.

But it seems that the Shamans weren’t the only ones to recognize the value of the Amanita muscaria. Several Russian travelogues have described celebrations held by high-ranking Siberian tribe members, where small doses of the mushroom were shared, much like alcohol would be in the West. These low doses would produce a sensation of warmth and increased energy, which one would assume would have brightened spirits amongst the cold, dark and bleak Siberian winters. So what does this have to do with Christmas, you ask? These mushrooms are a native of the Siberian forests, and Shamans would spend ample time collecting these precious fungi. Now this is where the uncanny ‘Father Christmas’ correlations begin to stack up.

Coincidence?

Firstly, the forests of Siberia are predominantly pine trees. And it just so happens that the Amanita muscaria mushrooms have a symbiotic relationship with pine trees, as well as birch and oak trees. As such, the Amanita muscaria can be found growing at the base of the majestic pine trees that cover the Siberian lands. Not unlike red-and-white wrapped gifts found at the base of a Christmas tree, which also happens to traditionally be pine.

The Shamans and laypeople would collect these mushrooms and go about drying them for use. Now, there were a few different methods for this. In the warmer months, this could be done by positioning them amongst the branches of a central pine tree that received direct sunlight. Pretty red-and-white decorations hanging from a tree…sound familiar? And if that isn’t enough, an alternate drying method was to place the fungi in a sock and hang them by the hearth. How interesting!

But the connections don’t end there. As the solstice drew nearer and the days grew colder and shorter, it is believed that Shamans would visit people’s homes to deliver and administer these magical, medicinal, dried mushrooms; these treasured gifts, to brighten the damp spirits of the families trapped in their cold homes. What’s more, due to the extreme winter conditions, the doorways to these dwellings would often be snowed in, so the only access would be through a hole in the roof, where the smoke from the fire escaped. You might know this as a chimney.

Exciting presents appearing under pine trees; pretty red-and-white decorations dangling from their branches, respected and adored men descending through chimneys with their red-and-white gifts, and socks with more treasures hanging by fires. The correlations are quite astonishing, but that is still not all! We haven’t yet addressed the unmistakable attire of our friend Santa, not to mention his trusty steeds.

Almost every Westerner knows Father Christmas wears a red, velvety suit with woolen or fur trimmings to keep the chills at bay. Many believe it began with Coca-cola, who adopted Santa as their jolly red and white mascot in the 1920s. Prior to then, Santa’s ‘look’ was inconsistent, and not the kind, round, white-bearded man we all recognize now. He was often depicted in a variety of ways and with varying attires; Elf-like, or tall and gaunt, sometimes wearing a bishop’s robe or a Norse huntsman’s animal skin. The Bishops robe and tall, gaunt look were likely influenced by Saint Nicholas, as that is how early doctrines described him. As for the ‘huntsman’ look, Siberian Shamans would wear coats of caribou (reindeer), so it is not unrealistic to speculate that this image was birthed here, and that tales of these deer-coated men, with their unusual winter solstice practices, spread far across Europe, and later the world.

And what about Santa’s reindeer friends? Well, Siberia has a large population of caribou or reindeer, both wild and domesticated, and early Siberians depended on these animals for their survival. Aside from their meat and their fur, they were used to pull sleds; an efficient and practical mode of transport in this snow-covered region of the world. It is thought that people who were hallucinating from the Amanita muscaria would believe the reindeer to be flying.

What to believe?

So what does this all mean? For a start, it clears up the many obscurities of Santa and Christmas, as we now know them. Upon researching, however, it became clear that there are a number of stories regarding Santa Claus’ origins, and though we can speculate until the reindeer fly home, one can never know the absolute truth of this tale. I would go so far as saying that most of these tales have at least grain of truth, and that each of them has contributed something to the evolution of modern day Santa. In saying this, I do believe that there is significant evidence to suggest that the Siberian Shaman legacy has been a strong influence. Perhaps it is simply lesser known because the customs and traditions of first nation people are, sadly, more and more a rarity, and consequently, their traditions are misconstrued and misunderstood.

Whether this Shamanic twist of the tale is, in fact, the beginnings of Santa or not, it seems that there are overlapping, and poignant, themes from both this and Saint Nick’s story; themes that speak of charity, love, connection and community. And in my opinion, this is the true essence of Christmas.

So, let us hold these special messages like the gifts that they are, throughout this festive season and beyond… Regardless of what you choose to believe.

Source: Uplift

You may also like:

What a shaman sees in a mental hospital

What it actually means to be a shaman & how the term has lost its way culturally